Israeli space tech prepares for blastoff

Could 2023 be the year that Israeli innovation reaches truly stratospheric heights?

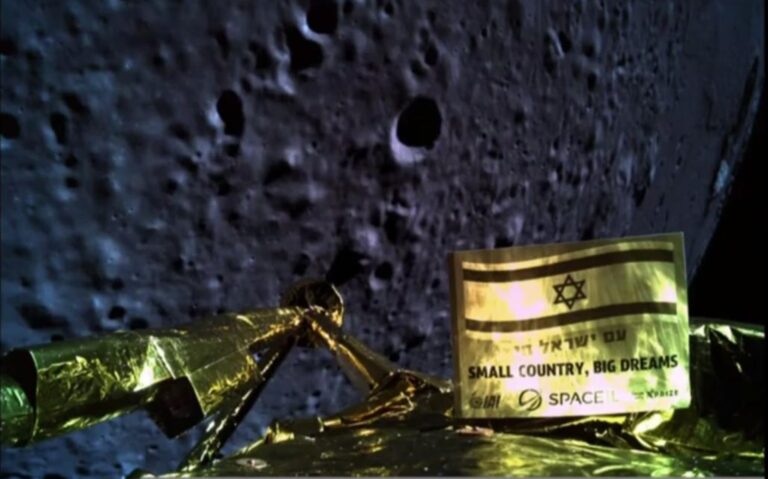

When Israel’s Beresheet lunar lander crashed onto the Moon in April 2019, Israel’s nascent space-tech industry didn’t mourn.

After all, tiny Israel is one of only four countries that has gotten a spacecraft that far – and plans immediately were hatched to launch Beresheet 2, with both a lander and an orbiter, in 2024.

Israel’s optimistic attitude to what would be perceived in more risk-averse nations as a career-busting disaster is not unique to space-tech, but it is a big reason why 2023 stands to be the year that Israeli innovation reaches truly stratospheric heights.

That will be aided in part by an Israeli government pledge to invest 600 million shekels (around $180 million) in the civilian space industry over the next five years to help it compete in a worldwide space economy that Start-Up Nation Central estimates at $400 billion.

The funding, which is being promoted by the Israel Space Agency, has sky-high goals:

- To quadruple the number of people employed by space-tech companies from 2,500 to 10,000.

- To increase total spending on space-tech projects from $1 billion to $1.25 billion.

- To increase the number of academic researchers in space-related subjects from 120 to 160.

- To increase the number of high school students interested in working in space-related fields from 200 to 4,000.

Space-tech incubators

The government can’t do all that on its own, of course. So, in recent years, private investors and incubators dedicated to advancing space-tech have cropped up.

One of these, Earth & Beyond, in collaboration with Israeli satellite telecom company Spacecom, won the government tender to establish the first Israeli incubator focused on space-tech startups.

“We want to be a part of the new space revolution,” says the incubator’s director, Ofer Asif, who’s also a senior VP at Spacecom.

“Our vision is that by 2030 there will be hundreds of ‘NewSpace’ startups employing 20,000 people. Groups such as ours will continue to invest billions in these ventures.”

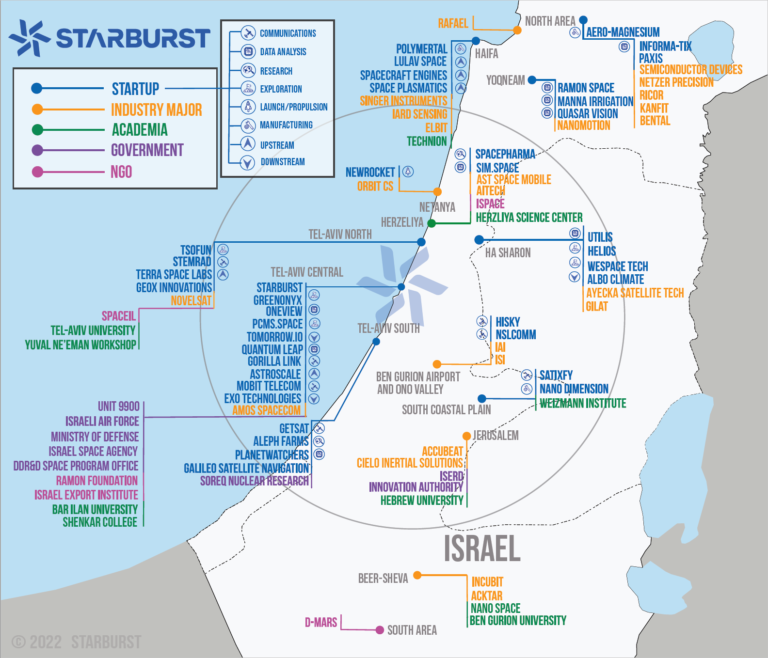

Astra, powered by IAI and Starburst, is Israel’s first space-tech accelerator designed to benefit the evolving space ecosystem in Israel.

Starburst also runs 13-week accelerator programs in Los Angeles, Paris and Singapore and a year-long accelerator program which Alliel says positions startups to be “three times more successful in raising their next rounds than others in the market.”

Israel managing director Noemie Alliel notes that among the categories Starburst invests in are regional mobility (including launchers and supersonic and hybrid flights); in-orbit infrastructure; and enabling technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and cybersecurity.

A brief history of Israeli space-tech

Israel’s space-tech industry got onto the map in 1988 with the launch of Ofek 1, the country’s first communications satellite. (Ofek 16 was launched in 2020.)

That’s not an insignificant achievement.

Only a few other countries can launch satellites: the United States, Russia, Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, India, China, North Korea, South Korea and New Zealand.

Moreover, Israel is the only country “to launch satellites in the other direction,” Hila Haddad Chmelnik, director-general of the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology (MOST), tells ISRAEL21c.

“All around the world, satellites launch from west to east. But we can’t launch to the east because of our neighbors, so we launch the other way, which loses energy. When you have less energy, you have to make the satellites smaller.”

The Start-Up Nation Central consulting group counts some 50 companies and academic institutions active in Israel’s space tech industry. Their common denominator: Doing more with less.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Alliel tells ISRAEL21c. “We don’t have a lot of cash. For Beresheet, we spent about a tenth of the cost of the cheapest landers from other countries. We were able to develop similar technology for a fraction of the cost.”

Israel has long punched above its population weight when it comes to an involvement in space.

Two Israeli astronauts have gone into orbit: Ilan Ramon, who died in the 2013 Columbia Space Shuttle explosion; and Eytan Stibbe, a former Israeli Air Force pilot and businessman, who paid to be a “space tourist” on the International Space Station in 2022.

Two Israeli astronauts have gone into orbit: Ilan Ramon, who died in the 2013 Columbia Space Shuttle explosion; and Eytan Stibbe, a former Israeli Air Force pilot and businessman, who paid to be a “space tourist” on the International Space Station in 2022.

Click here for a timeline of Israeli space milestones.

“Space is no longer the sole domain of the great powers or organizations, or a place only for science and research,” adds Uri Oron, director-general of the Israel Space Agency. “Space is now open for business.”

Down to earth

Space-tech today is not limited to pie-in-the-sky, Elon Musk- or Jeff Bezos-inspired spacefaring fantasies.

“The same technology can be used on Earth to produce iron in a much greener and cheaper way than current processes,” Starburst’s Alliel tells ISRAEL21c. “These are the kinds of companies we want to support. We don’t have to wait to get a colony on Mars to see a return on investment.”

“The same technology can be used on Earth to produce iron in a much greener and cheaper way than current processes,” Starburst’s Alliel tells ISRAEL21c. “These are the kinds of companies we want to support. We don’t have to wait to get a colony on Mars to see a return on investment.”

“We want to create a sustainable space economy for both life on Earth and beyond,” notes Einat Berkovitch, cofounder of TYPE5, an Israeli venture capital firm focused on investments in space. She spoke at the Israel SpaceTech Summit in Tel Aviv earlier this year.

Other areas of space-tech where Israel is moving forward include space robotics, pharmaceutical development in zero gravity, and developing quantum computing platforms in space.

SpaceIL’s Beresheet 2 spacecraft will carry a mini greenhouse with a range of seeds and plants meant to be grown on the Moon’s surface. The only crop that has ever been grown there so far is a single Chinese cotton seed, sprouted in 2019.

“Bases on the Moon or colonies on Mars could become a reality, and we’re exploring whether we know how to grow plants there,” explains Prof. Simon Barak of the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research at Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheva, which is developing the greenhouse in conjunction with universities in Australia and South Africa.

Downstream applications of space-tech can make a real difference back on Earth.

Observation satellites can, for example, help researchers “understand where pollution in the ocean is,” Haddad Chmelnik explains. “Or, by using pictures from space, we can analyze where there’s lithium around the globe.” (Lithium is a key component in most electric car and cell phone batteries. It’s becoming increasingly rare and expensive.)

Climate change is also on Haddad Chmelnik’s agenda.

“You can’t find all the solutions here on Earth,” she says. “As a result, space becomes very interesting. We can see what’s happening on Earth from the outside. We can measure the temperature of the water, for example.”

And of course, clandestinely monitoring what rogue states such as Iran and North Korea are trying to hide with their military programs is optimally done from space.

Financial services multinational Citigroup estimates that $100 billion will be invested in such downstream applications by 2040.

How Beresheet inspires While the Beresheet lander and its subsequent crash didn’t initiate Israel’s interest in space-tech, it may have been the country’s most high-profile endeavor.

Beresheet started as a response to the Google Lunar XPrize, which promised a $20 million grand prize for the first team to make it to the Moon and transmit back high-definition images and video.

The XPrize deadline expired in 2018 before any of the teams were able to launch, so the prize went unclaimed. SpaceIL, which built Beresheet with Israel Aerospace Industries and the Israel Space Agency, did receive a $1 million Moonshot Award from the XPrize Foundation in recognition of touching the Moon – even if it was in pieces!

But SpaceIL’s founders weren’t in it solely for the money.

Founded in 2011 by Yariv Bash, Kfir Damari and Yehonatan Weintraub, SpaceIL was always about “inspiration through action” and the goal was to get young Israelis interested in pursuing space careers.

Along those lines, the Israel Space Agency and MOST launched the TEVEL program about four years ago, giving an opportunity for Jewish and Arab high school students to build, test and launch nanosatellites into space, and then use them to gather data and conduct experiments.

Getting more women into the heavily male-dominated space-tech field is another goal for SpaceIL and for organizations such as WiSpace (Women in Space).

Regulating space

Business beyond the Earth’s atmosphere might become harder to achieve due to the growing problem of “space junk.” This is another area where Israel can take a significant role.

Satellites, when they’ve lived out their lifespan, remain in space. As a result, it is becoming difficult to find safe pathways that avoid a devasting collision.

Regulation of space traffic is therefore a high priority.

Neta Palkovitz, founder of space law, regulation and policy consulting group NewSpace Firm, explains that “there are five space treaties, UN resolutions and guidelines, all aimed at regulating space activities,” including the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs and the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

However, current treaties are “only between space-faring nations and not commercial businesses” like Elon Musk’s SpaceX or Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, Palkovitz says.

States can take their space squabbles to the International Court of Justice, but commercial entities don’t have standing there, Palkovitz notes. “So, right now, if there is a dispute regarding space activities, there is no specific place to go to solve things without involving states.”

Abu Dhabi Space Debate

On December 5, Israeli President Isaac Herzog delivered a keynote address at the Abu Dhabi Space Debate in the United Arab Emirates.

The conference brought together national and industry leaders to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing the global space economy.

Herzog said he believes “the greatest promise of space exploration lies not only in discoveries on distant planets, but also in rediscovering our potential for collaboration, here on the blue planet we call home.”

Herzog noted that Israel enjoys close cooperation with NASA, the European Space Agency, and counterparts in France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Brazil and other countries. Its evolving space partnership with the United Arab Emirates, he said, is “boldly leading our region toward new frontiers in space and leaving our mark on history.”

One example he cited was the Venus satellite, a joint Israeli-French project now providing data for joint Israeli-Emirati research.

“The Venus satellite has been circling Earth closely monitoring vegetation in forests, croplands, and nature reserves, and beaming back multispectral images. In their first joint venture, the Israeli and Emirati space agencies are now funding a joint analysis of this data by Israeli and Emirati scientists, which will help us better understand our global environment and collaborate on new solutions to protect our planet’s green lungs.”

To infinity… and beyond?

So, will 2023 be the year that space-tech takes off in Israel?

“This is one of my main goals,” says Israel Space Agency chairman Dan Blumberg. Perhaps Israel will even be invited one day to join the European Space Agency to further future collaborations.

“We definitely have the potential to be a leader, but more things will need to fall into place,” says Alliel.

Hila Haddad Chmelnik is feeling more positive.

“To deal with space, you have to be really optimistic,” she explains. “So, yes, the next year or two will be significant for Israeli space tech. I hope 2023 will be the year!”

Check out our timeline to the moon here.